34 days after the incident, yesterday Viasat published a statement providing some technical details about the attack that affected tens of thousands of its SATCOM terminals. Also yesterday, I eventually had access to two Surfbeam2 modems: one was targeted during the attack and the other was in a working condition. Thank you so much to the person who disinterestedly donated the attacked modem.

I've been closely covering this issue since the beginning, providing a plausible theory based on the information that was available at that time, and my experience in this field. Actually, it seems that this theory was pretty close to what really happened.

Fortunately, now we can move from just pure speculation into something more tangible, so I dumped the flash memory for both modems (Spansion S29GL256P90TFCR2) and the differences were pretty clear. In the following picture you can see 'attacked1.bin', which belongs to the targeted modem and 'fw_fixed.bin', coming from the modem in working conditions.

A destructive pattern, that corrupted the flash memory rendering the SATCOM modems inoperable, can be observed on the left, confirming what Viasat stated yesterday.

After verifying the destructive attack, I'm now statically analyzing the firmware extracted from the 'clean' modem. Firmware version is 3.7.3.10.9, which seems to date back to late 2017.

Besides talking about a 'management network' and 'legitimate management commands', Viasat did not provide any specific details about this. In my previous blog post I introduced the theory that probably 'TR069' was the involved management protocol.

Obviously, I can't completely confirm this scenario but I'll try to elaborate my reasoning.

Attacking via a management protocol

I think there are two main options: either the attackers abused a MAC management protocol or an application layer one.

For the MAC case ('ut_mac' binary), in general terms, the attackers would have required an even more privileged access to either the NOC or the Ground Stations, probably in a persistent way via malware. I guess that this kind of privileged access would have been enough to limit the attack to Ukraine, instead of knocking out half Europe. As a result, I'm inclined to think this was not the case.

On the other hand, a 'misconfigured VPN' that enabled the attackers to reach the 'management segment' and execute 'commands' seems to be more related to an application layer management protocol: SNMP or TR069.

SNMP

An initial analysis of 'vsatSb2Ut.so' shows that the implemented MIB does not seem to provide the required functionality to perform this kind of attack.

I would initially discard this option.

TR069

As suggested in the previous blog post, the Surfbeam2 modems are deployed with the Axiros' AXACT client. The nature of the operations performed by TR069 clients makes them very convenient for an attack of this type.

cwmpdefault.xmlBy reverse engineering the 'cwmpclient' binary it is possible to recover the Viasat's TR069 data model, analyze how it has been implemented as well as how it communicates with other components to perform the required actions (via IPC queues).

So far, I would highlight the following features/issues:

1. * Updated *

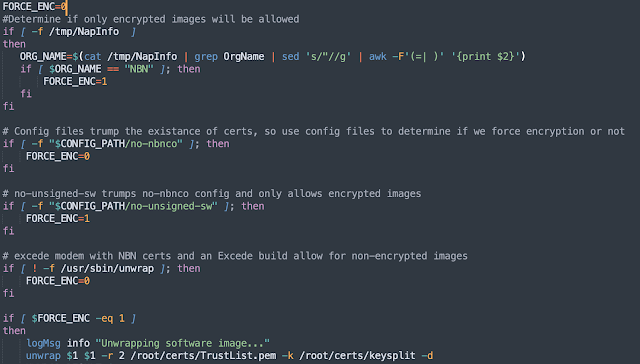

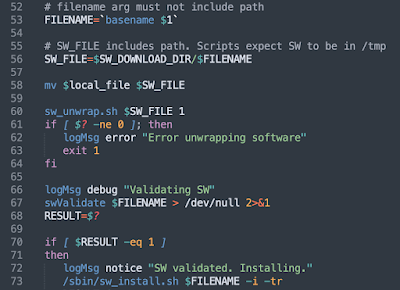

As the analysis is ongoing I want to clarify that new firmware may be cryptographically validated, after being downloaded by the TR069 client. It depends on the configuration of the terminal, according to 'sw_unwrap.sh'

If the signature is not enforced, then the firmware image is just validated against a CRC via 'swValidate'

...

swValidate (implemented in 'ut_mac' binary)

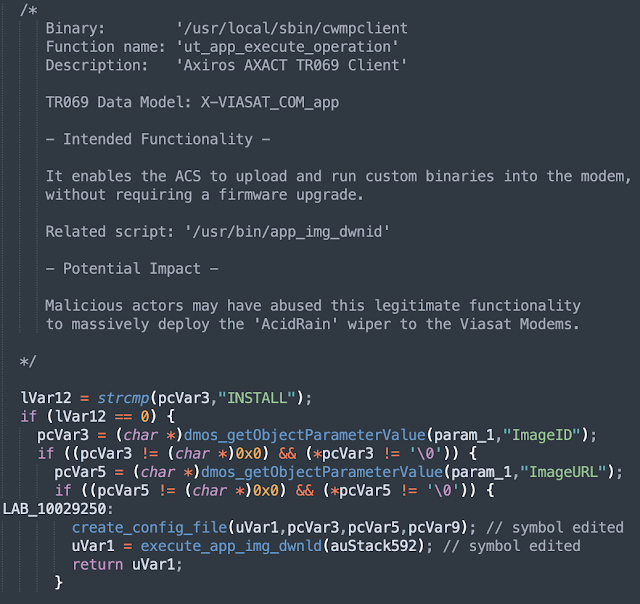

2. * Updated * 'APP INSTALL'

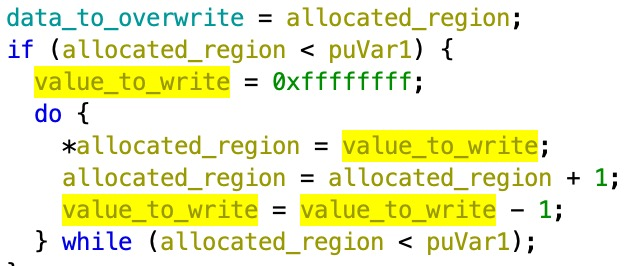

A deeper look at the 'ut_app_execute_operation' function revealed that it is implementing a functionality that enables the ACS to install (upload and run) arbitrary binaries on the modem, without requiring either a signature verification or a complete firmware upgrade.

This functionality seems to match both the Viasat statement as well as the approach to deploy the 'AcidRain' wiper described by SentinelOne.

'/usr/bin/app_img_dwnid'

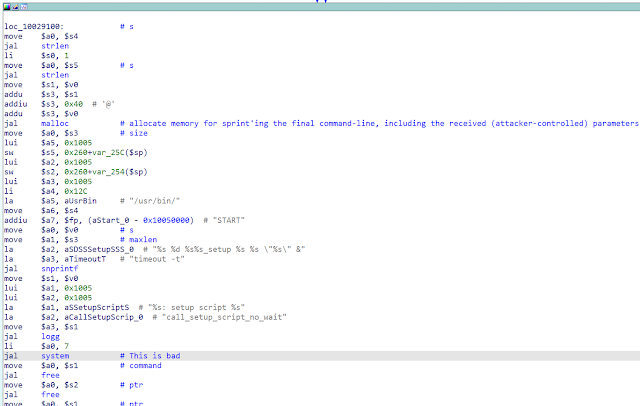

Command Injections

Additionally, there are multiple command injection vulnerabilities that can be trivially exploited from a malicious ACS (or someone with the same privileged position in the network).

i.e 'ut_app_execute_operation' for the custom 'Device.Services.X_VIASAT-COM_app' object ('cwmpclient')

Conclusion

There are similarities between these issues and the approach followed by the attackers in the Viasat incident, especially the TR069 'APP INSTALL' feature, but I am not implying that any of these techniques were actually abused by the attackers. However, overall the security posture of the Surfbeam2 firmware does not look good.

Hopefully these vulnerabilities are no longer present in the newest Viasat firmware, otherwise that may pose a security risk.

There are several unknowns yet to be resolved.

1. How the initial compromise of the VPN appliance worked. Did the attackers have valid credentials (maybe stolen from either Skylogic or its partners) or they exploited a known vulnerability (assuming an 0day doesn't match a 'misconfigured VPN appliance' explanation )?

2. How exactly the attack propagated to other countries, lasting for several hours. One of the affected persons I talked to got his modem knocked out around 9:00 am (GMT+1), several hours after the initial attack.

3. Before the destructive payload was executed, there was any other kind of malicious code running in the modems for a short period of time? Sentinelone published a very interesting research on 'AcidRain', a wiper that is able to generate the same destructive pattern observed in the modem's flash memory.

Coincidentally, this wiper also has similarities with 'VPNfilter' malware.

4. Did the compromise of the management segment involve additional attacks besides the VPN issue?

Unfortunately these technical questions can only be answered by people with an insider knowledge. Let's see if Viasat is willing to provide further details on this case.

* Updated - The VPN Attack vector*

Viasat has not elaborated the VPN attack vector yet, but they acknowledged to journalists that the attack originated from the Internet. Viasat is also distancing itself from the fiasco by directly pointing to Skylogic and its ground infrastructure.

Although we're entering again the land of speculation, there are some factual bits that should be considered.

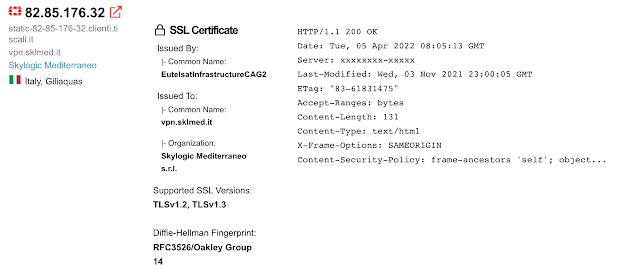

A simple recon of Skylogic's ground network (AS201935) reveals a couple of interesting things:

1. Skylogic relies on Fortigate appliances

'cgl-fw02' may be indicating the Skylogic's Cagliari teleport.

2. The route propagation matches the attack. Viasat's statement explicitly mentions that the attacker moved laterally until reaching the management network.

It is also worth mentioning that, in 2021, there were different attack campaigns and leaks targeting Fortinet VPN appliances. These attacks were carried out by groups of malicious actors that exploited multiple vulnerabilities that were discovered in these products.

Viasat's statement mentions a 'misconfigured VPN appliance', so if we consider that this definition may be a euphemism for an 'unpatched VPN appliance', then we may have a plausible attack vector. It is also possible that malicious actors may have previously collected valid VPN credentials as a result of these attacks.

Another interesting aspect that Viasat implicitly introduces in its statement is the potential security weaknesses that may be derived from the complexity of wholesale operations for a Satellite infrastructure. Down in this chain we find ground station operators, satellite service providers, distributors , resellers...

At some point they all need certain kind of access to provide their services, so this integration also may pose a challenge in terms of security. For instance, a publicly exposed server provides a glimpse of the Eutelsat's partners API capabilities.

In general terms, it is also recommended to not expose an operator's desktop in corporate videos. It usually leaks information that may facilitate different kinds of attacks.